For most of us, vermouth is that dusty bottle in the back of our liquor cabinets, reserved for that one time a year when we decide to try our hands (yet again) at being martini people. Little do we know of the history and artistry that has culminated over centuries to bring this unique fortified wine into our homes.

In this post, I’ll break down exactly what vermouth is, its history, styles, and how to best serve and enjoy this exciting aperitif!

The History of Vermouth

Vermouth is, simply put, an aromatized fortified wine. Its history dates back to Piedmont in the 1700s when it was developed as a medicinal treatment.

The original recipe consisted of a base wine infused with a secret blend of aromatic spices, barks, bitter herbs, and flavorings, including everything from anise to bitter almond, chamomile, ginger, quinine, and saffron, to name a few. While many of these ingredients are used today, one noticeable absence is wormwood, which was banned due to its psychoactive effects.

Fun fact: The name vermouth comes from the German wermut, or “wormwood.”

While originally used for medicinal purposes, vermouth quickly became a popular aperitif, served in cafes alongside espresso. In the late 19th century, it became a key ingredient used in cocktails ranging from the Manhattan to Negronis and martinis.

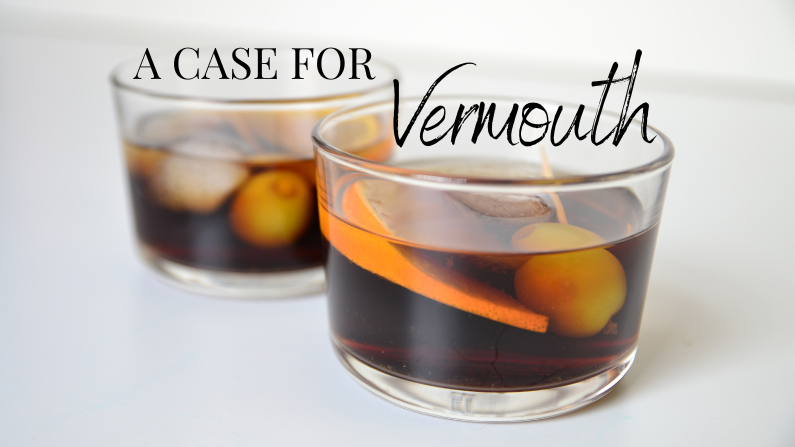

The concept of vermouth as a standalone drink has largely died down, with the exception of Spain, where it is still widely served in cafes, restaurants, and bars, typically with ice and an olive, orange peel, or lemon peel.

How Vermouth is Made

Vermouth begins as a dry, still wine, typically made with white grapes. The Piedmontese originally used muscat grapes, though today, cheap red or white bulk wines are used, which has unfortunately led to a drop in quality.

After the still wine is infused with a proprietary blend of aromatics, it’s fortified to raise the alcohol to 15-21%. If it’s a sweet style of vermouth, cane sugar or caramelized sugar are added. It’s the caramelized sugar that gives red vermouth its color, as most vermouth is made with white grapes.

Different Styles of Vermouth

There are three main styles of vermouth–along with lesser-known styles–that are slowly growing in popularity. Here’s a quick breakdown:

Sweet vermouth

Also known as red or rosso vermouth, this is the most popular style. It’s made primarily from white grapes, with caramelized sugar or caramel color added to give it its signature red hue. The average sweet vermouth contains around 130-150 grams of sugar per liter.

Sweet vermouth is the style called for in Manhattans and Negronis due to its strong fruity, herbaceous, and spice notes.

How I recommend drinking sweet vermouth: On the rocks with an orange peel or with equal parts Campari and soda water to make an “Americano.”

Dry vermouth

Dry vermouth is, as the name suggests, vermouth made with little to no added sugar. It’s clear and best reserved for martinis. Compared to its sweeter counterpart, dry vermouth is more floral, tart, and lean.

The maximum amount of sugar allowed in dry vermouth is 30 grams per liter, though most styles have little to no sugar. If you’re desperate to avoid sugar at all costs, opt for an “extra-dry vermouth.”

How I recommend drinking dry vermouth: Straight with an olive, just as you would a martini. It’s my go-to swap when I’m craving the flavor of a martini but less alcohol.

Blanc vermouth

Also known as blanco or bianco vermouth, this semi-dry style hovers around 50-90 grams of sugar per liter. Its color ranges from white to amber or golden. Blanc vermouth typically has subtle honey and vanilla notes, making it a unique species that doesn’t quite fit in with a Negroni or martini.

How I recommend drinking blanc vermouth: On ice with tonic.

Rosé vermouth

A relatively new phenomenon, rosé or rosado vermouth is becoming a popular choice for rosé lovers and mixologists looking to experiment. Rosé vermouth is typically semi-sweet or sweet, with around 90-130 grams of sugar per liter. The flavor of rosé vermouth varies, with more floral, raspberry, honey, and grapefruit notes.

How I recommend drinking rosé vermouth: Chilled, straight, or mixed with tonic.

Tips for Serving and Drinking Vermouth

The market for vermouth has been dominated by big-name brands pedaling oxidized bulk versions of an otherwise delicate and vibrant drink. If you can, I highly suggest seeking out a smaller-name maker and trying to taste the difference.

In the meantime, here are a few tips to help get the most out of your next bottle of vermouth:

- Treat it like wine

Unlike Madeira, vermouth has a shorter lifespan, so it’s best consumed within two months of opening.

- Store it in the refrigerator

This will help preserve its freshness for longer and delay oxidation.

- Try it as a standalone drink

Add a little ice and garnish. Trust me, you won’t regret it!

Olivia is a Washington-based freelance writer with a Level 2 Award in wines from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust. She has a passion for all things food, wine, and travel, though her heart belongs to the Pacific Northwest. When she’s not sipping on a glass of Washington Cab., she’s usually bikepacking, crocheting, or chillin’ in the sun with her dog Tater.

IG: @liv_eatslocal

Website: liveatslocal.com

0 Comments